In 2023, Blists Hill Victorian Town is celebrating its 50th Anniversary. Since it opened in 1973, the museum has grown significantly as local buildings have been rebuilt or copied at Blists Hill to recreate a small industrial town. The museum aims to show what life was like living and working in the East Shropshire Coalfield around 1900, but what can be seen at Blists Hill today is very different to how the site looked in the 19th century.

From the late 18th century until the 1950s, Blists Hill was an industrial site. At its peak in the 1850s we believe more than 700 hundred men, women and children were working in the noisy and smoky environment of Blists Hill where iron chains clanked, steam-winding engines thudded, and horses laboured transporting materials and goods.

Bedlam Furnaces, Philip James de Loutherbourg (1740-1812), hand-coloured aquatint, 1805.

Roads in 18th century Britain were usually poorly maintained muddy tracks, so many industrialists built canals as they were much more efficient for transporting goods and materials. The industrialists of Shropshire were no different and in 1788 an Act of Parliament was passed that allowed the Shropshire Canal to be built. This canal would link the mines and ironworks of the East Shropshire Coalfield to the River Severn by passing through Madeley and Blists Hill, before descending the slopes of the Ironbridge Gorge to join a length of canal alongside the river at Coalport. The most difficult issue for the canal engineers to solve was the method of descending the hill to Coalport. Using the conventional lock system on this hill would have required travelling through twenty-seven locks over three hours which simply was not quick enough.

The story of industry at Blists Hill begins about 30 years before any industrial activity took place on the site. In 1757 twelve local industrialists, merchants, and gentlemen decided to construct the Madeley Wood blast furnaces alongside the River Severn. These furnaces are better known as Bedlam Furnaces and the company who managed them became the Madeley Wood Company. In the 1780s, the company and its furnaces were taken under the control of the Reynolds family, who were local industrialists, entrepreneurs, and philanthropists. In the same decade a member of this family, William Reynolds (1758-1803), decided to sink a mine at Blists Hill to access the rich seams of coal, ironstone and clay that lay under the site. The coal and ironstone were supplied to the nearby Bedlam furnaces to be smelted into pig iron, but Reynolds needed an efficient method to transport them.

A view of the Hay Inclined Plane from the canal at Coalport, late 19th century.

The owners of the canal, the Shropshire Canal Company, held a competition in 1788 to find the best solution to this problem. This was presented by James Loudon, a surveyor for the company, and Henry Williams, an engine erector working for the Coalbrookdale Company. Their plan was to remove boats from the water and place them into cradles, which would then be raised up or lowered down the hill on rails, initially using hemp ropes and horse and manpower, but later using wire ropes and steam power. It was to be known as the Hay Inclined Plane. The inclined plane was an ingenious solution to a serious engineering problem and allowed boats to be lifted down the hill in just four minutes. The canal opened in 1792, followed by the inclined plane in 1793, and tub boats were soon leaving Blists Hill laden with coal, ironstone and clay.

In 1797, William Reynolds took over management of the Madeley Wood Company, which included the furnaces at Bedlam and its mine at Blists Hill, and was assisted by his nephew, William Anstice (1781-1850). They worked together until Reynold’s death in 1803, after which William Anstice took full ownership of the Madeley Wood Company. The company remained in the Anstice family until the 1920s.

[Left] Posthumous portrait of William Reynolds (1758-1803) after an original, attributed to William Hobday (1771-1831), oil on canvas, c.1816. [Right] William Anstice (1781-1850), oil on canvas, date unknown.

For the next 40 years, the mine at Blists Hill continued to supply raw materials to Bedlam furnaces until they were replaced by new blast furnaces built at Blists Hill between 1832 and 1844. This new site was close to the canal, which provided a method of transporting goods and materials, and to the mines at Blists Hill, which supplied the raw materials for smelting pig iron. Initially these blast furnaces were very profitable, and production peaked in 1871 when 11,500 tonnes of pig iron were produced.

By 1847 the Madeley Wood Company had also built a small brickworks at Blists Hill, which took advantage of the clay that was being mined there. Initially the works produced handmade bricks and roofing tiles but in the 1870s there was a considerable expansion of the works and the brick and tile making process became increasingly mechanised. This reflected what was happening in the industry across Britain in the second half of the 19th century as the demand for bricks and roofing tiles rose. Industrialisation, with its housing and factory developments, and growth of road, railway, and canal systems, produced an ever-increasing demand for bricks and tiles.

Blists Hill blast furnaces during the time that they were nearing their peak production, 1860s. The three men in the foreground give a sense of scale to size of these works.

Across the country, brick production doubled between 1850 and 1900, and by the end of the 19th century brick was the main building material in nearly all areas of Britain. The expansion of the Blists Hill brick and tile works in the 1870s allowed the Madeley Wood Company to mechanise the brick and tile making process and therefore speed up production. In a year, their workers could make around 1 million bricks or 5 million tiles.

As well as being a site of industry, there were also 20 cottages at Blists Hill. Most have been demolished and were located where the museum’s car park is today, whilst the remaining cottages lie outside the museum site. These cottages, built by the Madeley Wood Company in the 1830s, were mainly occupied by people who worked in the iron, clay, and mining industries at Blists Hill. The cottages were relatively isolated, being located about a kilometre from the centre of Madeley and with no shops or places of worship nearby. There were, however, two pubs close by that were frequented by the cottages’ inhabitants: the Pheasant Inn, which is now closed, and the All Nations, which is still open today. The cottages were very basic and some families were raising as many as 10 children in these simple homes. Each cottage had a kitchen/living room and small pantry on the lower floor and two bedrooms on the upper floor. Wash houses were at the end of each terrace and four outdoor toilets serviced all 20 cottages and their numerous residents.

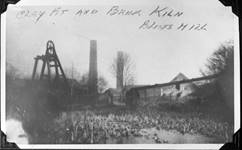

Blists Hill’s industrial peak arguably occurred in the early 1870s, when the blast furnaces were their most profitable and a new mechanised brickworks was developing. However, this decade also saw the start of the site’s decline. It was during this decade that Blists Hill’s mine stopped producing ironstone and coal. Brick and tile clay continued to be mined and used by the adjacent brickworks, but the Madeley Wood Company had to begin sourcing its raw materials for Blists Hill’s blast furnaces from further afield and in 1872 built the Lee Dingle bridge to transport materials from Meadow Pit colliery in Madeley to Blists Hill’s furnaces. The mine at Blists Hill continued to operate but by 1900 only 12 people were employed there and following the First World War it was sold several times. Abandonment plans were discussed as early as 1925 but it wasn’t until June 1941 that the mine was completely abandoned, and the shaft was filled in.

A boiler being removed from Blists Hill's blast furnaces following their closure, c.1917-1918.

Blists Hill’s blast furnaces also suffered declining profits from the 1870s. By this time, the furnaces’ technology was old fashioned, but its cold-blast pig iron filled a niche in the market. However, like most of the Shropshire iron industry, it was facing competition from cheaper imports of iron from Europe and America and competition from the steel industry. The lack of raw materials being mined at Blists Hill and the subsequent need to transport them from further afield also increased costs. In 1908, two of the three furnaces were blown out (ceased operating) and following a national miners’ strike in 1912, which severely impacted the supply of raw materials, the final furnace was blown out. By this time, the Madeley Wood Company’s profits were coming from coal mining rather than iron or brickmaking and so they also sold their Blists Hill brick and tile works to George Legge & Sons in 1912. Under George Legge & Sons the works produced handmade and specialist products alongside their mass-produced bricks and tiles and continued to manufacture these products until 1938, when the company was liquidated. From 1945, sanitary pipes were made at the works but this ceased in 1956 and the works was closed.

With the closure of the sanitary pipe works, more than 250 years of industrial history at Blists Hill was brought to an end. The ruins of the industrial works that once thrived at Blists Hill were scattered across the site and were rapidly being reclaimed by nature.

However, as we all know, this was not the end of Blists Hill’s history. By the late 1960s the importance of Blists Hill’s industrial past was being recognised and the future of the site was secured. You can find out more about the origins of Blists Hill as a museum here.

Blists Hill blast furnaces in the second half of the 20th century before any conservation work was carried out.